I love the business side of branding. To my surprise, I discovered long ago that I share this perspective with many board members of companies I’m working with. Instead of looking at the ‘magic’ of branding, they’re much more interested in the ‘logic’. This is, by no means, meant to disrespect the ‘magic’ — the creative side — of branding; it’s crucial for any brand to form some sort of an emotional bond with its audiences, for which you need the creative side. However, I find that for boards to make decisions on what, where, and how much to invest in the brand, it is key to have the more ‘logical’ side of branding prevail at the boardroom table. To give some insight into how brands are being debated about in the boardroom, I’ll be sharing my top considerations on branding from a boardroom perspective in a series of articles. This is the first article in the series, looking at the business side of branding.

‘Brand equity’ doesn’t exist in the boardroom

For brand marketers and communicators, brand equity is all about orchestrating the intangible relationship between brands and their stakeholder groups. Naturally, these are often customers or clients, and increasingly other audiences such as employees, suppliers of products, services, and capital, and society as a whole. The extent to which brands generate more preference, loyalty, or ultimate value, is referred to as brand equity. Looking more in-depth, this can be split into brand drivers, the ingredients that make up brand equity. Marketers around the world are educated to understand these mechanisms and to operate them in real life — the science and art of marketing.

In the boardroom, however, brand marketers and communicators do not always have a seat. On the contrary, most boards consist of non-marketers or no marketers at all. More often, the common denominator for backgrounds of board members stems from finance, business, and increasingly from IT and digital. Also, the boardroom ‘language’ is financial and factual, and not marketing language. It’s the language of the capital markets, the economy, and 100% captured in systems for financial reporting; be it IFRS, FASB, or US GAAP or whatever regulations apply for a listed company.

The appearance of the brand in a balance sheet

So, here’s the thing: In a balance sheet, ‘brand equity’ is not visible, it doesn’t show. You can see ‘Brand’ under Intangible Assets, at the top-left of a balance sheet. And you can see ‘Equity’ under Capital, at the top-right of a balance sheet. For both ‘Brand’ and ‘Equity’, the financial community has been working for hundreds of years to create a framework of definitions — so practitioners understand exactly what’s what (the first book on this was by L. Pacioli in 1445). They are two different things altogether, for this community.

So, what happens if brand marketers or communicators bring up ‘brand equity’ in boardroom conversations? They run the risk of being misunderstood. The same applies when they start talking about ‘brand in the balance sheet’, as that is mostly interpreted to only be in the balance sheet when a brand has been acquired from another company, and only then when the buyer has decided to keep it. Internally developed brand value can never be shown on a balance sheet. This is why, for example, the brand value of LinkedIn is shown on the balance sheet of Microsoft, whereas the brand Microsoft itself — funny enough — is not.

As a manager of the brand, by not adhering to the business language of a topic, you immediately start off on the wrong foot and might be disconnected from the business conversation. Also, you’re effectively reinforcing the image of the marketing and communications domain; that it’s about spending money and value only comes into the equation later.

Translating data into insights

This is also a plea for data, data, and data. In the digital age, we have access to tons of data and this should be interpreted and translated into insights. Whenever I consult on rebrand programs, one of the key areas is investigating what we can learn from data, which then becomes a crucial input for the program. For example, when merging the banking activities in the Baltic states for DNB and Nordea, data showed that the new name, Luminor — a new generation bank, would really work well with local audiences. Similarly, when rebranding travel agency Arke to TUI, we knew that 50% of the turnover was online, and to convert that, many A-B tests were conducted to ensure a seamless transition for website traffic. Data also taught us how much money to invest in performance-based marketing.

My recommendation here is to always speak about the brand as the most valuable intangible asset and to demonstrate how this asset can support business performance, which is why I love the business side of branding. On average, brand value represents around 20% of the market capitalization of the top 500 companies in the world (Brand Finance).

If you are able to demonstrate how brands generate value and can orchestrate the intangible relationship between an organization and its stakeholders, you will be heard in the boardroom. After all, exhibiting this relationship is not an easy, one-dimensional thing, but it’s what board members understand. Achieve this and I predict that you will instigate questions like, ‘Okay, how does that work then and what do we need to get it right?’. And right there, the journey of making the business case and roadmap for your brand growth begins. This thinking will enable you to sketch out the why, what, and how to go about this, and to obtain the mandate that goes with it to start your journey. You’ll soon be coordinating the brand to drive business performance. And isn’t that the most valuable brand purpose?

Cover image source: Razvan Chisu

*By Marc Cloosterman, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

“The ultimate resource in economic development is people. It is people, not capital or raw materials that develop an economy.” — Peter Drucker

The world economy is being shaken up. Business has to rewrite the economy forecast at completely different terms and market conditions. People are scared and trying to adapt their lives to the conditions imposed by the crisis — they are wearing protective gear, stocking up on essentials, limiting their social contacts, and working from home.

More than ever, people need help to survive — physically and mentally. More than ever, businesses will need help to recover. Now is the time, companies and people, to rethink our relationships, rethink the way we act, and start all over again with the mindset of understanding, selflessness, and compassion.

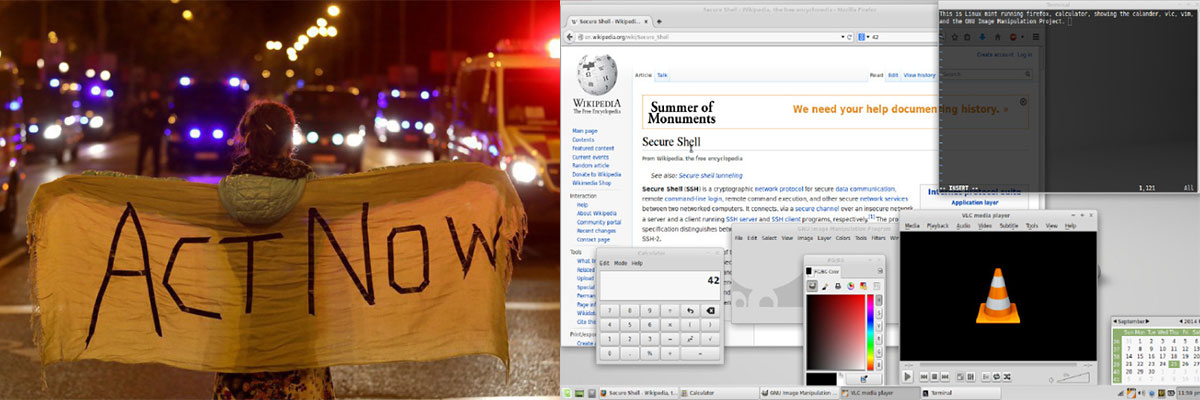

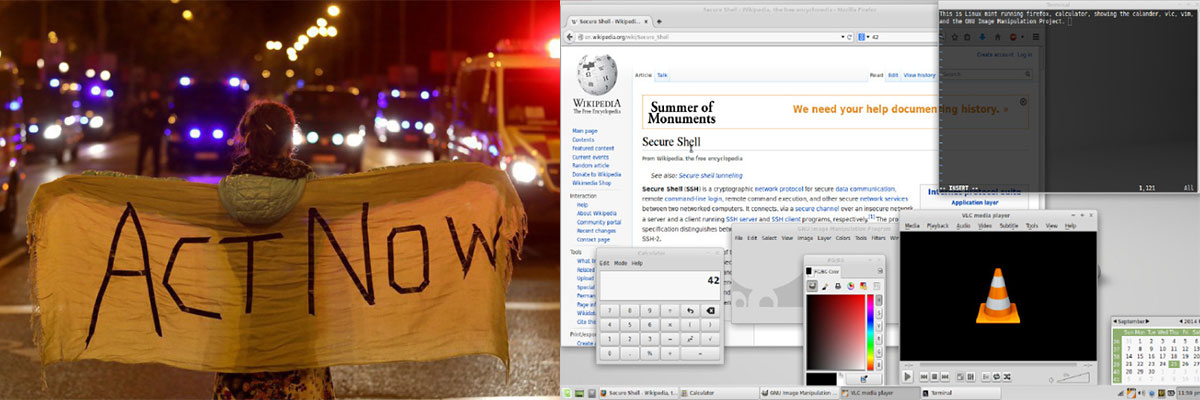

Left: El Pais Madrid, Víctor Sainz, Dec 2019

The march coincides with the United Nations climate summit in Madrid, which protesters hope will entail specific measures to stop global warming.

Right: Wikimedia Commons, Benjamintf1, Sep 2014

A screenshot of Linux running Xfce desktop OS, Mozilla Firefox browsing Wikipedia.com, a calculator, calendar, Vim, GIMP, and the VLC player, all of which are open-source software.

Our world is evolving in turbulent changes. Shaped by globalization and new technologies, business ecosystems have changed dramatically — it’s all hyper-competitive. And now came more stress of an economy in crisis. People are scared, and yet, their worldview is more significant than ever. The fear of epidemics and social limitations, coupled with new tech, communications, and the Internet, is creating a new customer mindset — the world has become even smaller and more social. In a time under pressure, after the ‘new normal’ comes the ‘next normal.’ But where are the companies and organizations?

People are pressured by uncertainty in the economy, politics, and the environment, they do not believe in organizations and don’t want to be just observers anymore.

Widespread internet access and the use of social media have empowered people. They don’t care about the media, they are the media. Now, time is a forcing factor and people don’t have time to pay attention to ads, rather they want to be part of everything that happens. The examples of the new way of thinking are the success of the open-source model and open-collaboration projects such as Bitcoin, TEDx, Google X, and Wikipedia, the high popularity of vlogs and podcasts, the role of influencers in public opinion, the extensive use of YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, and other social media owned by people. Brands are no longer what is said in ads, but what people say. People are no longer a target in the marketing plan, but any successful company should be a part of their plan.

The keyword is CHANGE. Business models adapt to new customer demands and take customer value to a new level. For the business, it is still fundamental to deliver value to its customers, but what is valuable today? The definitive way to find out what customers value is to ask them. Letting customers take the lead, this is the milestone in updated customer relationships. Marketing is being transformed into an open-collaboration system. The task of communication is to invite people to participate in it.

The New Opportunity

Restrictions on marketing communications open up new opportunities. Competitiveness will no longer be achieved by talking about the company, the product, and its benefits.

What has been described here is not the end of marketing communication, but an opportunity for a fresh start. The steadily declining potency of the traditional advertising toolkit has been pushing marketers into a new territory of brand-customer relationships. To be relevant, advertisers today cannot speak of products as unique and amazing because they are not unique and amazing anymore. There are at least several competitors in each business sector that offer the same product at the same price. Therefore, spreading the next product-benefit story is a surefire way to lose customer interest.

The cycle “Make a product, promote it, sell it,” is spent and running less and less. Customers take a good product for granted and expect a new level of offering. That is why, from now on, successful companies will offer people not just products and product benefits, they will offer care and compassion.

Nike’s support of Kaepernick’s cause made many people rebuke the company as anti-American and literally burn their Nike sports shoes, but many have appreciated Nike’s civil position and demonstrated that they share the same values.

Source: Twitter, Sean Clancy, 2018

An example is Nike’s position as an activist for racial equality. In 2018, they sparked a strong public reaction with a commercial featuring an American football player Colin Kaepernick, who began kneeling during the US national anthem in NFL games to protest police shootings at unarmed black men — a gesture that drew the ire of President Donald Trump.

The position the company took was political and social, nothing to do with the goods they sell. Connectivity comes from Nike’s core value — spirit dedication above all, and the slogan of the campaign “Believe in Something. Even if it means sacrificing everything,” expresses this value strongly. The spirit is above rationality. The campaign led to a public crisis and many people were angry with the company, but many people showed solidarity towards the company’s position.

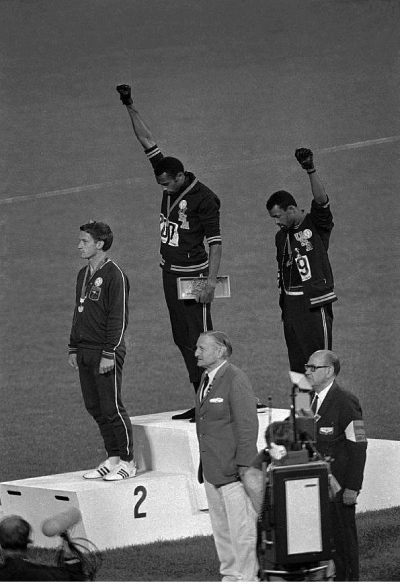

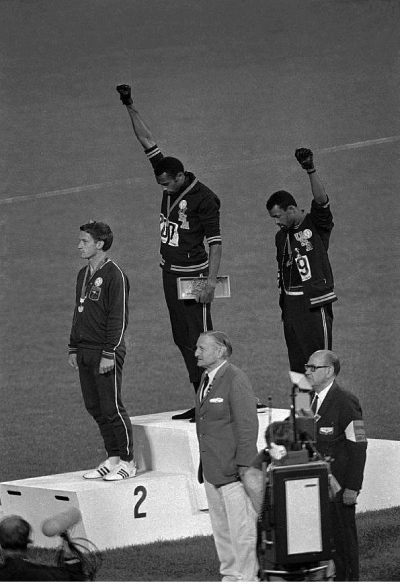

Source: Wikimedia Commons, Angelo Cozzi (Mondadori Publishers), Oct 1968

Puma, with its #REFORM campaign, also used the publicity of the sport as a tribune for social justice. The campaign commemorated the 50th anniversary of the intolerable-for-its-time Black Power salute of African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, at the 1968 Olympics. The two raised hands in black gloves symbolizing racial inequality in America, a social problem valid to this day. Puma CEO Björn Gülden said: “We are not trying to make commercial advertising out of this, it is part of our values.”

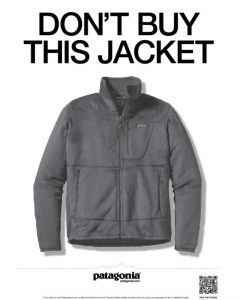

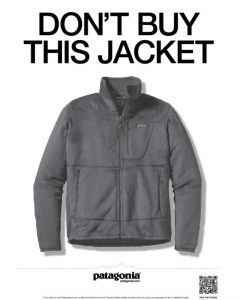

Another example: In 2011, the outdoor-clothing company Patagonia ran an ad page in the New York Times stating “Don’t buy this jacket!” Patagonia was, probably, the only company to encourage its customers to NOT buy during Black Friday, the annual peak on the American market.

The Black Friday ad that Patagonia devised to urge its customers not to buy their products.

Source: patagonia.com

The ad provides a list of reasons why the jacket should not be purchased. For example, the production of a jacket requires 135 liters of water, equivalent to the daily needs of 45 people. Or the fact that the entire production route of the jacket generates nearly ten kilograms of CO2. Even for a jacket created with high environmental standards, the environmental cost is much higher than its actual cost. “Don’t buy what you don’t need,” said the ad. Repair, reuse, recycle. With its position as a sustainable, value-driven company, Patagonia resonates with a growing worldwide readiness to change social, economic, and environmental processes for the better. For its customers, Patagonia is a promise. Patagonia’s sustainable position tripled its revenue between 2008 and 2015, rising to $750 million.

Customer care and shared company values are a new level of customer relations. They outline a new approach in marketing communications that enables companies to make a profit by creating common good, with the support of their customers. Instead of promoting products and benefits, the company can create an ecosystem of the brand and its community. This community will not only share and promote but will live by the brand’s messages because it believes in them.

Source: Reuters, Predirick Valenzuelavia, Dec 2019

The 11-years old Filipina champion with self-made Nikes. The brand community is not made of people wearing branded shoes but of people living the brand spirit.

Cover image source: Ben White

*By Ivan Gurkov, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

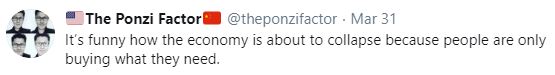

Marketers have an uncanny ability to redefine words and frame situations in their favor. The current global situation is no different. I’ve received a flurry of emails over the last week, aimed at convincing me that buying products I don’t need is an act of “solidarity” and “being in this together.” I wish I was more surprised. The relationship between crisis and opportunism is as old as time, but we should demand better.

Image source: Tan Liu (@theponzifactor)

A virus, by nature, attacks and capitalizes on weakness. We are seeing weakness in our government, public policy, healthcare systems, and consumerism. Why would brands not also be exposed? After all, we’re in this together, aren’t we? When celebrities respond by posting sing-along videos why wouldn’t your favorite brand assume that offering a discount is akin to helping out? Their true underlying values and raison d’etre are being exposed by the hour and the actions of these celebrities, companies, and brands during this crisis will not be forgotten after the pandemic.

“To question the doing-well-by-doing-good-globalists is not to doubt their intentions or results, rather it is to say that even when all those things are factored in, something is not quite right in believing they are the ones best positioned to effect meaningful change.”

― Anand Giridharadas

I’m sure you’ve seen at least a handful of “togetherness sales” and “solidary sales.” For many brands, the definition of “being in this together” has always referred to the intersection of their product or service and your money. The strategy of a lifestyle brand is — essentially — to convince you to define the value of your life with their brand. While many would argue this definition in crass, I hold that a pandemic is no time for mincing words. Now, in the face of a global crisis, these same lifestyle brands are choosing to pivot that strategy by inauthentically adopting the character and tone of a caregiver archetype.

The strategy is to create a perception of solidarity. But it’s hollow when your platform is a coupon for 15% off silk blouses or a discounted ticket for a cruise ship under quarantine. In order to truly be a caregiver brand, you need to care more about helping your customers move through this crisis than moving your dead stock. Empathy and compassion must permeate your every action. And you had to start yesterday, not tomorrow. If you aren’t offering meaningful and relevant information and solutions, then you are distracting from true solidarity.

Attempting to co-op solidarity is criminal. Solidarity is not a sales pitch. It is a battle cry, an ethos, and a bond between working people everywhere to band together against the hierarchical systems that seek to exploit them. Solidarity is about bolstering each other up in the face of maltreatment and persecution. It means locking arms in service of one another, not for a lifestyle brand. Companies and employers have no claim on solidarity, it belongs to workers who have spent the last 100+ years fighting, bleeding, and dying for it. Don’t disrespect the people, or the lasting severity of this pandemic by trying on language that is in direct conflict with your brand’s true interest.

“It is we who plowed the prairies,

Built the cities where they trade,

Dug the mines and built the workshops,

Endless miles of railroad laid,

Now we stand outcast and starving,

Mid the wonders we have made,

But the union makes us strong.

Solidarity forever.”

— Ralph Chaplin

In a world where cause marketing — the act of investing in social good for the purpose of advertising — is a regular extension of every marketing plan, and altruistic capitalism is the go-to move for billionaire PR spins, why should we expect a crisis to bring out better behavior in brands? We probably don’t, but we should.

Now is not the time to badger your email lists and social media followers with veiled offers and coupon drives. It is the time to offer real value to your customers, many of which lost jobs and are staring down the barrel of 6-8 weeks without pay, if not longer.

“Aim above morality. Be not simply good, be good for something.” — Henry David Thoreau

Everyone is going to take a hit, but maybe your brand could take that hit in a way that is actually useful. Instead of marking your non-essential products down 15%, you could donate to food banks, hand out hygienic gift bags, provide supplies to medical personnel, and offer materials or your manufacturing capabilities to produce the much-needed medical equipment. Invest in solutions and discount products that are actually useful for home quarantine and cleanliness efforts.

Stay at home but get involved with the people and cultures that make your business possible, rather than just pandering to it. With the ongoing school closures, streaming services could offer kids content for free. Fast-food restaurants could offer their entire menu as 2 for 1 drive-through-only. Grocery stores could find ways to offer free delivery or curbside pickup. Everyone else could hire at least a couple of laid-off workers to work remotely.

Solidarity will never belong to a brand. It belongs to the people, and those people really need help.

Image source: Elizabeth Lekas

*The article was originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

A number of years back, the word ‘disruption’ was handed a new lease of life. Delivering a new raison d’etre and identity to countless entrepreneurs, disruption is now an innovation phenomenon with a David-and-Goliath storyline: The small company with limited resources targets an overlooked segment of the market and uses technology to challenge the large, established businesses.

In best-case scenarios, this leads to gaining a foothold in the market and ultimately leaving the incumbent giant staggering.

I believe that dissonance is emerging as the packaging design’s latest disruptive tool. Dissonance is more likely to be picked up by small brands since large, long-established brands usually build their messaging around broad appeal and, as such, are less willing to take risks. It’s the smaller brands, the newcomers and the niche, who are likely to leverage a little-loved design trend to gain standout. There’s a lot to be learned from dissonance, from its fine art origins to the way designers access it, to when a great idea can go terribly wrong.

Image source: The Dieline

A Storm in a Teacup?

Painters and sculptors have long used visual dissonance — perhaps most notably in the genre of Surrealism — to activate a state of psychological tension and to confront onlookers with their own unfulfilled expectations, forcing them to register a disparity between what they expect to see and what they actually see.

Surrealist René Magritte famously manipulated dissonance in a series of groundbreaking works that subverted the status quo through the misnaming of objects, doubling, repetition, mirroring, concealment, and depictions of visions seen in half-waking states. However, Surrealism’s most notorious example of visual dissonance is Mere Oppenheim’s fur-lined teacup — a piece that has been triggering lust, laughter, disgust or delight for nearly a century now.

These works demand attention and catapult our intellectual effort far beyond the casual glance. Onlookers must resolve the tension, or simply abandon the piece altogether. While some resolve the conflict by simply turning away, denying the sensory impressions, many onlookers will try to overcome the dissonance through cognitive means, i.e. taking a closer look.

Image source: The Dieline

Harnessing Visual Dissonance

The evolution of ultra-precise production technology has provided packaging “artists” with nearly limitless capabilities, and in effect this has been the chief enabler of purposeful dissonance.

Flawless printing has allowed textural design techniques, as the pack face approximates a non-traditional material so authentically that the consumer is momentarily thrown. Beauty brand Clé de Peau’s luxury-fabric box front was created by premier Japanese kimono-fabric designers for an utterly unique, realistic appearance. Another excellent example is Kasper Ledet’s experimentation with texture and obscurity for Danish craft brewer To Øl. Quality printing permits dissonance, such as on a spirits container which claims, ‘This is not a luxury whiskey,’ a Magritte-esque statement which would be believable if not for a faultless, high spec finish.

The importance of precision and balance can be verified by the way musicians employ dissonance to provoke attention and manipulate mood. An expertly performed chord of irregular, clashing orchestral music leads to a sense of satisfaction in the listener once the harmonic notes follow, however permanently dissonant music is usually too difficult for the listener to bear. Without balance, the dissonance overwhelms, and the power in the contrasting consonance is lost.

Likewise, if we take the use of blur as an example of dissonance in packaging design and examine what makes a label, which appears to be an obscuration of a figure behind it, actually work, we may point to the perfect balance of colour and white space, the crisp logo and font serving as the anchor, permitting the dissonance. If you fall foul of flawed elements, don’t be surprised when your customer leaves the bottle on the shelf.

Image source: The Dieline

Image source: The Dieline

When Dissonance Goes Wrong

We have to be stringent as to what constitutes ‘dissonance,’ and prevent ourselves from describing every creative new design as dissonant, just as we can’t call every innovation ‘disruption.’ To truly use dissonance, there has to be that tension, those flashes of hesitation, cognition, resolve. It’s worth remembering too that we live in a world where emotions are cultivated for profit, and the use of aesthetics to activate micro-stressors hedges towards the unethical. Triggering a jarring feeling or confusion within the consumer calls for responsible handling — the aim isn’t to distress, it is to tell a story.

This year, in particular, we should give credit to those who break the mould. Pantone has presented us with possibly the safest color choice in a decade — and in this era, brands are likely to embrace wide appeal and opt to reassure rather than challenge. In picking up the dissonance trend, there’s more than one tightrope brands and designers will walk.

But then again, being the disruptor was never going to be easy.

Cover image custom tailored by Equator Design for this exclusive article.

*The article was originally featured on Brandingmag.com.