In the last decade, retail has gone through more crises and subsequent periods of stagnation, with a marked shift in favor of the online channels and consequent reductions in sales points, the number of employees, and the profitability of companies (even large ones). The sectors most severely affected are restaurants, tourism, clothing, and furnishings.

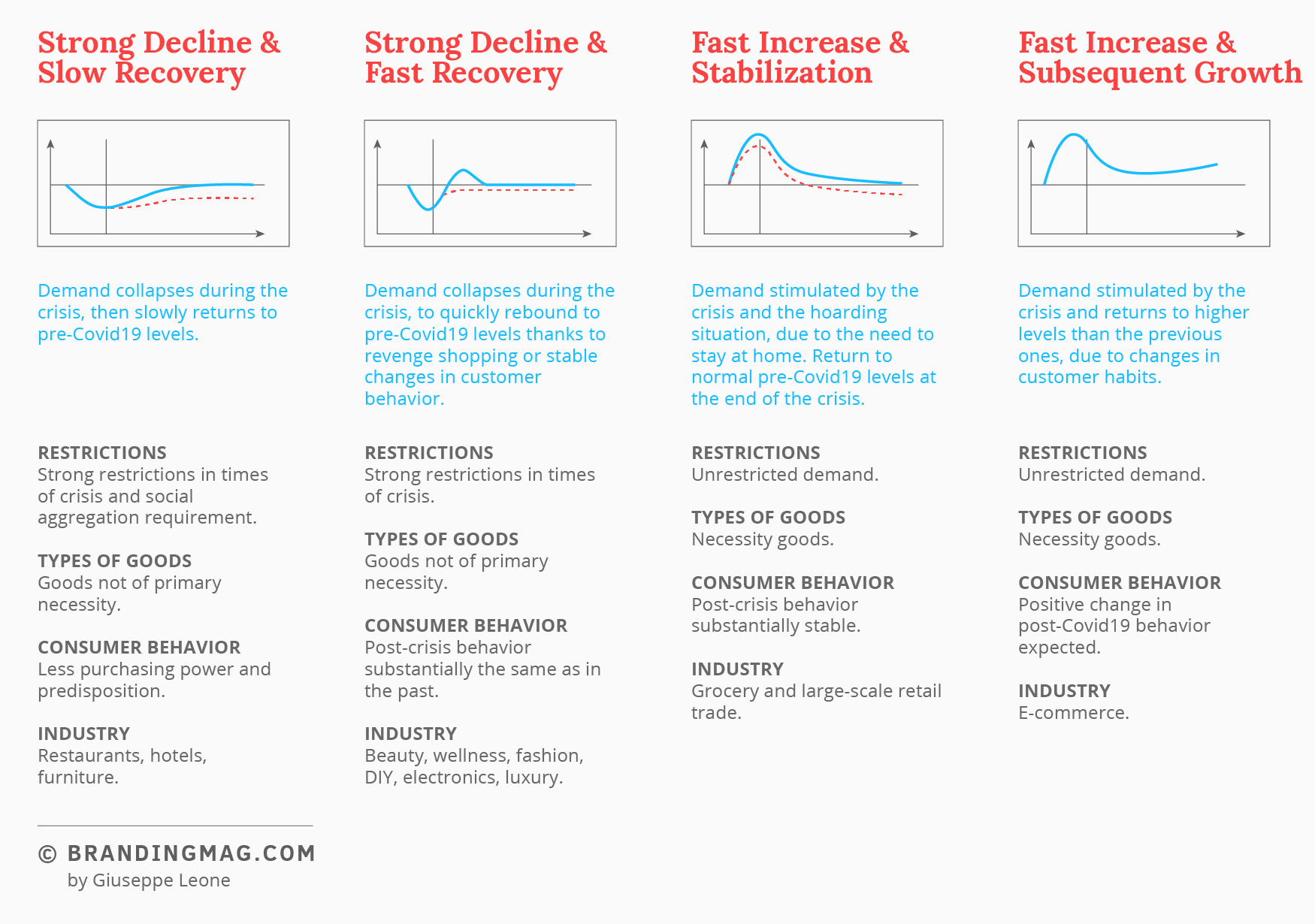

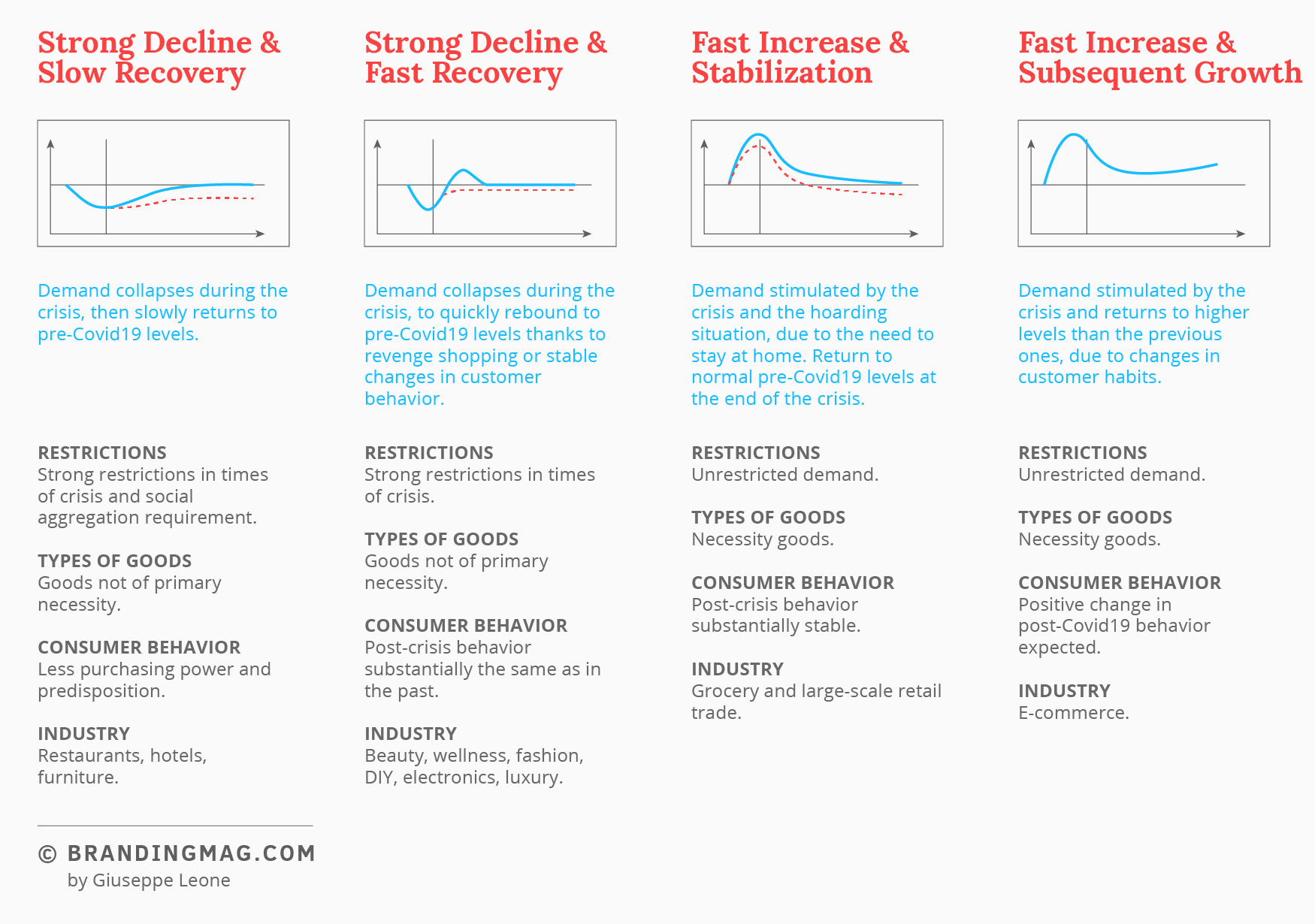

In detail, the impact of COVID19 in the sectors under analysis in terms of trends will see different dynamics among them, according to three main variables:

- level of the expected movement restrictions in the coming months;

- type of goods sold;

- changes in purchasing behavior and expenditure availability (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 — New market scenarios and post-crisis demand trends

Apparel will suffer damage in 2020 due to the seasonal leap, the difficulty of aggregating typical traffic in the points of sale, and the difficulty of starting the supply chain. The recovery is likely for 2021, but not to such an extent as to recover this year’s negativity, also thanks to the effect of the revenge shopping that could accompany the recovery of consumer goods and impulse (think about what is already happening in China).

The furniture sector will also suffer a negative trend this year, and probably also next year, since, as happened in the past, the reduced purchasing power given by the economic crisis is reflected in the postponement of purchases of durable goods by consumers.

Coming to the beauty & wellness segment, a fairly rapid recovery is expected with the increase in the desire to take care of the image and look, as well as the wellness side linked by a double thread with the health and hygiene aspect.

Among the sectors a little less exposed in the short and also in the medium-term, drugstores should not suffer a particularly negative effect, given their traditional role of strong convenience and for the wide spectrum of basic necessities.

Consumer electronics has been maintaining only a partial sales activity in recent weeks (for those who have kept it open), given the common difficulties of movement and accessibility to the points of sale, with recourse to “massive” online. Post-reopening is expected to recover, but the impact on the year will still be heavy and the strong pressure on margins that online entails will lead to tensions on profitability.

Finally, the large-scale retail trade that today (and for the next few months) is growing strongly due to the role of basic necessity, benefiting largely from the substantial total absence of competition given away from home, and which will instead have to deal with important changes in consumption which will impact the various channels, already visible today (hypermarkets in further sharp decline, e-commerce boom, further strengthening of discounters, rebirth of the neighborhood).

Coming to e-commerce, in 2021, post-crisis, it will rise in level by making a step up towards market penetration higher than past forecasts, which will cover all sectors analyzed. In recent weeks, the use of online has accelerated strongly for basic necessities/goods that you need to have at home, much less obviously (but only for a short while) for other types of impulse/luxury goods, where the use of online delivery is now the only option to buy.

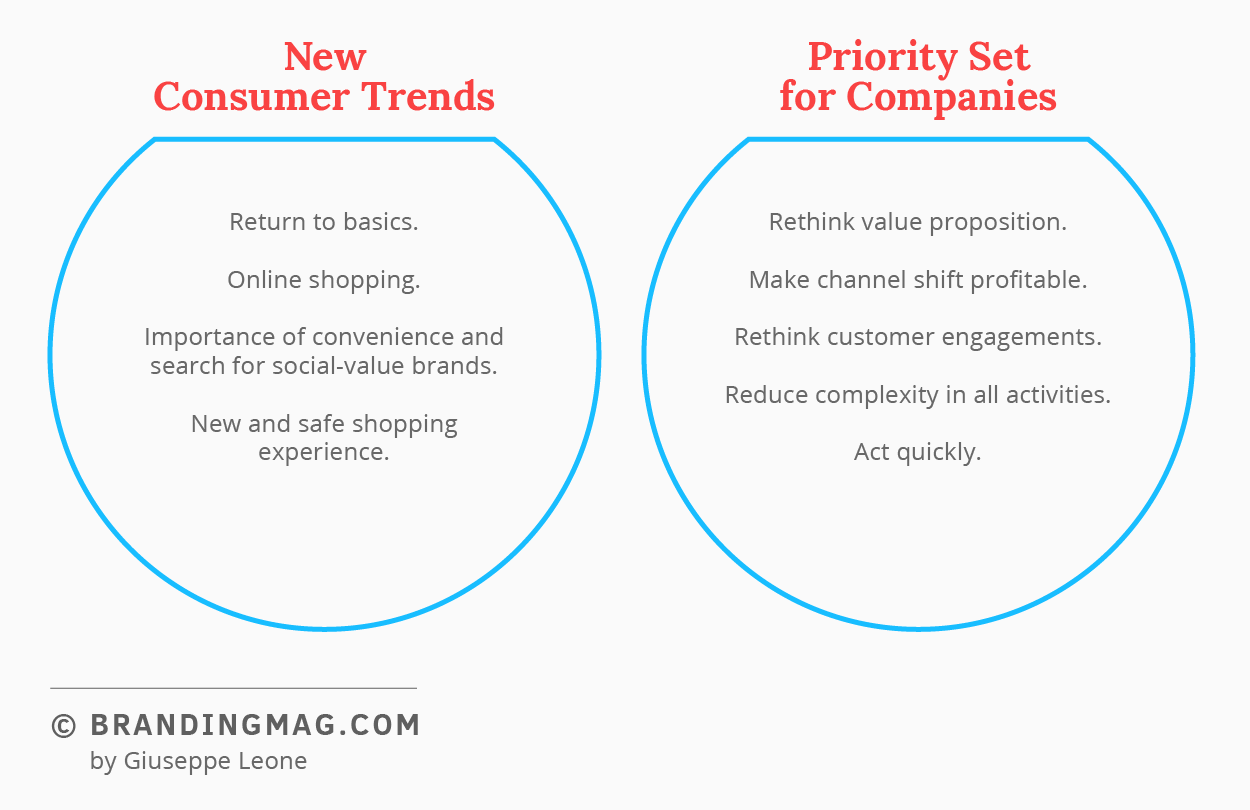

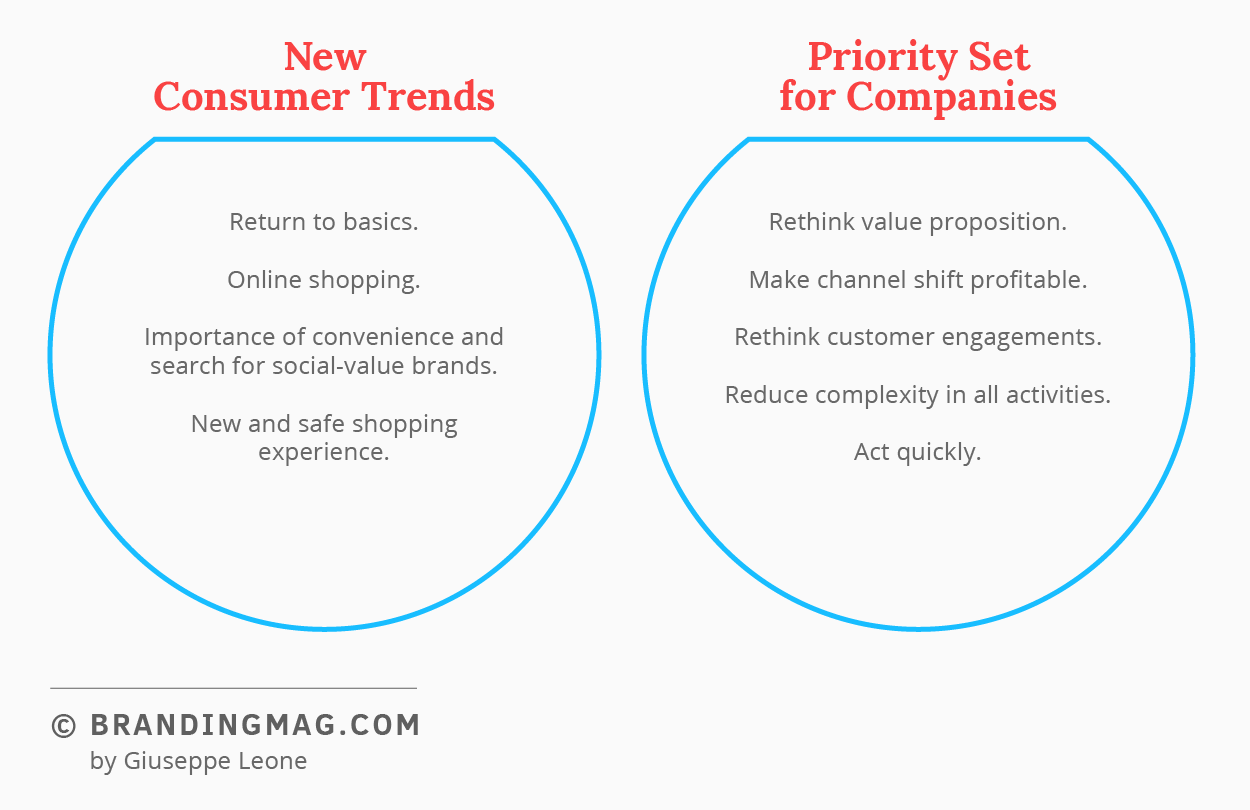

New consumer trends or acceleration of pre-existing trends are shaping with a rapidity never seen in a new market landscape. There are four key macro-trends in consumer behavior that open new scenarios for companies (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2 — Consumer trends and new priority set for companies

Consumers returned to the basics

Panic-buying focused on nondiscretionary products needed to sustain governmental shelter-in-place orders, including shelf-stable food items, healthcare products, and cleaners. Many households did not store food and household items in an amount necessary to overcome even short supply shortages. This experience of scarcity and under-preparedness for disasters will likely impact our consumer behavior going forward, and it may also make many consumers consider keeping safety stock inventory at home on an ongoing basis.

Online shopping spiked globally week-over-week

The forced closure of physical stores resulted in a pivot to e-commerce, with consumers securing essentials by any means necessary. In terms of behavior changes, the rise in online buying, specifically for groceries, is noteworthy. Among all age groups, there is a large segment of consumers that tried online grocery buying for the first time in March, and many will likely continue to buy groceries online, at least as long as the pandemic continues. Of course, it is impossible to foresee whether a large share of consumers will remain loyal to online shopping or go back to the brick-and-mortar stores once they feel safe to do so. Most of us have missed the social experience of shopping for many weeks now, and the convenience of the online channel may not make up for this.

Importance of convenience and search for social/intrinsic value brands

The economic crisis will amplify income disparities; overall, all consumers will be price-sensitive and cautious in spending, given uncertainty about the future. Greater importance is attached to the intrinsic value of the products. Authenticity and purpose (intended precisely as the objective that each brand aims to pursue on a social level) are the most relevant value pillars for the current consumer and to which brands must respond. It is no wonder, in fact, that consumer expectations require brands to be helped in daily life because they are close, becoming reassuring, but above all compassionate and supportive, as an expression of a true, authentic, and growing common collective interest.

Amplified and safe shopping experience

Growing desire of shoppers for a more amplified in-store experience that combines security and a sense of community.

From these trends derive crucial areas of intervention that brands should face in the next period for profitable growth:

Rethinking the value proposition

With the change in consumer preferences, the winning brands will be those that will better understand the new needs of their target. Leveraging on big-data analysis, brands should quickly mobilize to create a distinctive omnichannel experience and analyze purchasing data through specific data-mining techniques to generate new sub-segments of customers and orient their choices in a win-win perspective of consumption.

Rationalize and make online business profitable

The new consumer habits, resulting from the lockdown measures, have shifted demand towards online channels, and have led to an inversion of roles of the two channels (“channel shift”). This contingent situation can irreversibly change the behavior of customers, whose habit of making purchases online, overcoming the initial rigidities and fears, can translate into ‘normal’ behavior again, assuming a routine character. Companies will have to strengthen their presence on digital channels and optimize the experience lived by customers, with particular reference to new adopters.

Rethink customer engagements

As we all practice social distancing, communication is more important than ever. This is an opportunity for more creative, authentic, and personalized interactions with customers. Retailers must meet shoppers where they are now — i.e., in digital channels via social, mobile, apps, etc. They should consider virtual events such as personal styling and how-to classes via video conferencing or live-streaming product launches to engage with shoppers.

Reduce complexity in business

Retailers were forced to simplify their activities during the crisis; this forced experiment provides a unique opportunity to challenge the entire cost base, reducing complexity and increasing flexibility and resilience.

Act now

Given the dynamics of the market, retailers must adopt a more reactive mentality and play upfront, to make bold choices by redefining their overall portfolio. In other words, it is essential to plan “now” and to act “now” to face the best start, without being surprised by the competition.

Cover image source: Clay Banks

*By Giuseppe Leone, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

The production, collation, and consideration of 1,200 post-it notes of information may sound like ‘data overload’, but the depth of detail that can be uncovered from this exercise — plus the visual impact of the resulting findings — will deliver unparalleled insight. Such insight is of particular importance when attempting to fix a broken culture.

This may not sound like an obvious brand-driven project, certainly to people who work outside of the creative industries. But if we remember a point that strategic brand professionals constantly stress — that brand is not about the logo — it’s soon easy to see the role that brand and design thinking could play in an exercise of this nature.

An educational challenge

To give context, it is helpful to consider a recent project to understand the current ‘state of play’ within an organization that is potentially on the verge of crisis. A design-focused approach was adopted from the outset to uncover the true situation — not just perceptions — and suggest opportunities to improve the internal culture before the future could be tackled.

This business operates in the education sector, although the methodology undoubtedly applies to virtually all private or public firms. In this particular example, the organization faced a seemingly relentless challenge to attract more and more students, with less and less funding, while maintaining exemplary quality standards, and all in the face of mounting expectations, a pressurized teaching climate and ever-advancing competition.

The senior leadership team identified that following a period of significant change — and with further change inevitably on the horizon — this was a great opportunity to go back to basics. It was a chance to answer questions such as ‘who we are’, ‘what are our principles’, ‘what do we stand for’, and ‘why are we different’.

If organizations can’t understand and remember all of that, how can they go on a journey together? And, equally, how can they bring others — such as students and their parents — on the journey with them?

Exploratory workshops

This sets the scene as to why all the organization’s 230 colleagues, from the senior leadership team through to part-time administrative staff, were invited to attend a series of workshops, as were a number of students, governors, and other educational partners.

The group sessions sought to explore what is great about working for the organization, what it is renowned for, how it compares in the marketplace, and what could be improved, to name just a few themes.

To ‘warm up’ the participants’ openness to all-things-brand, they were initially invited to align their organization to a well-known supermarket, writing just one word on a post-it-note to explain their selection. While the exercise was initially met with resistance — not least because supermarkets and colleges are markedly different — the resulting discussion was very telling. For example, it soon became clear that singular words such as ‘quality’ could have extremely varied meanings from one person to the next, evidencing that brand is open to interpretation and what defines it is often a myriad of things.

The core post-it-note exercise followed. Questions were purposefully simple, typically asking for one-line or even one-word answers to ensure participants did not overthink their responses. People were told to note their points, relatively privately, on colored post-it notes, before being invited to stick them on large sheets of paper that covered every wall in the room. This exercise followed the principles of the ‘rose-thorn-bud’ methodology, with the pink post-its (roses) representing what was good about the organization, green (buds) demonstrating the opportunities, and the blue (thorns) showcasing the lesser positive points, which could perhaps form part of the root cause of the broken culture.

Distilling the findings

The 1,200 post-it notes were then clustered to allow salient points to be presented back to the senior leadership team, in a separate session, away from the college. This clear methodology gave context to a mass of data and helped contextualize what may otherwise have been considered an overwhelming volume of information.

Importantly, ‘theming’ the 1,200 pieces of brightly-colored paper in this manner, meant they could easily be mapped against the organization’s currently articulated mission statement and values. This provided a really powerful, digestible, and effective way to distill the breadth of information down to a handful of must-know points. It also allowed the post-it-notes to do the talking — it couldn’t be dismissed as feedback from an external party that doesn’t truly understand the organization. And it clearly demonstrated that while the college may say certain things, these points perhaps don’t ‘show up’ in the eyes of the people who matter — the employees.

Every identified mismatch, however minor, was seen as an opportunity for change, a chance to review a potentially outdated value or practice that could otherwise contribute to a feeling of unauthenticity if it remained unaddressed.

What’s next?

The organization’s proposition — most notably its purpose, principles, and personality — is currently being rearticulated so that it can be replayed to everyone in the college as they move towards their future. It is hoped that, by rediscovering and redefining who they are, there will be a far greater chance of unity behind a shared vision, which should take people on the journey and encourage their collective appetite for change.

Again, visualizations will be crucial to conveying the new narrative back to the wider organization, with posters around college offering just one way to tell the story. This story won’t make external pressures go away. It can’t deliver a rapid fix. But it will hopefully help the organization rediscover its mojo, rebuild morale, and drive productivity and efficiency as they navigate the road ahead, together.

Involving some or all?

Meeting with a body of people — on this scale — is admittedly not an exercise for the fainthearted. But it needn’t be laborious, time-consuming, or restrictive in terms of timescales either. It can — and should — be fast and furious.

In the example above, groups of 20-30 individuals gathered in back-to-back discovery sessions which ran over 2-3 days and resulted in the unveiling of a significant amount of insight.

Would the same trends have been extracted if only a sample of people had been considered? Perhaps, if that sample was truly representative. But perhaps not.

Also, would the eventual ‘buy-in’ to any resulting project be as strong if only certain people felt consulted and therefore invested in the change project? Again, perhaps not, particularly in the cases of fixing a broken culture.

Sometimes, timescales or resources may dictate that sampling is genuinely the only option when undertaking such stakeholder research. But if this option is chosen because it is merely deemed a quicker fix, it must be accepted that the successful evolution of the brand project may be jeopardized.

To proceed or not to proceed?

Investing in the support of an external brand specialist may be the last thing on an organization’s mind when trying to rebuild a broken culture, especially if the situation is reflective of a business in crisis and potentially limited financial resources. To an extent, this is perhaps understandable.

However, the cost of not resolving the situation is undoubtedly far higher.

So, whether professional help is sought to mend a broken culture or not, the investment of time needed to undertake this visualization exercise and involve every impacted colleague, is certainly not something that should be avoided.

Cover image source: Victor He

*By Darren Evans, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

“Rest in Peace” posters of Dr. Li Wenliang, who warned authorities about the coronavirus outbreak, seen at Hosier Lane in Melbourne, Australia; by Adli Wahid.

Until the Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1912), Japan would have been defined by words like samurai, kimono, geisha, and others associated with its folklore. Japan’s industrial revolution opened space for a new world and word: modern. However, Japanese modernity only became memorable when associated with brands like Hitachi (1910), Panasonic (1918), Fujifilm (1934), Toyota (1937), Sony (1946), and Sony’s Walkman (1979) among many others.

The unspoken truth, however, is that the Meiji era held a powerful metaphor — the era of light. Meiji means “Enlightened Rule”, a construct that lent itself to a deliberate, state-led industrialization policy. A reenergized “brand Japan” enabled the development of new commercial brands, just as much as the latter helped validate the metaphor Japan came to represent, in a mutually reinforcing relationship.

These metaphors represent the mental associations and constructs we create when thinking of those nations just as much as how their inhabitants may see themselves; these are their place brands. Speaking with Professor Sohail Inayatullah, UNESCO’s Chair in Future Studies, who recently worked on the education futures of China, he said that metaphors present themselves as the main causation drivers of the future.

Metaphors like Hippocrates’ “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”, or Shakespeare’s “Clothes maketh the man” are just as powerful to informing our sense of self as the more modern “I buy, therefore, I am”. In fact, even the briefest exposure to the Apple logo can make you behave more creatively, according to research led by Professor Gavan Fitzsimons from Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. In this case, the apple on Apple’s logo is a metaphor for creativity or, as stated on the brand’s slogan, “think different”. The transformational power of metaphors (or brands) goes even further. Cardiologist and author Sandeep Jauhar explains, during the TEDSummit 2019, that our emotions impact the health of our hearts — causing them to change shape in response to grief or fear, to literally break in response to emotional heartbreak — demonstrating the impact of what is metaphorically felt over a very tangible reality.

When considering the world’s geopolitical volatility and the ongoing pandemic, protecting the way others feel about your nation — especially for brand China — has never been so important. And investing in a nation’s brand appeal pays back. For instance, back in 2012, Mexico’s President Felipe Calderon hired nation-branding expert Simon Anholt, for strategic advice in order to improve the nation’s image. By 2019, Mexico became America’s top trading partner.

Nation-branding goes beyond just telling your country’s story well, as China’s propaganda apparatus has been doing for a while now; it’s about crafting a narrative that reshapes reality.

Soft power with hard metrics is a means, not an end

While the virus is the real issue, the Chinese government’s naive attempt at protecting its image through poor conduct in communicating and responding to the disease was what ignited mistrust, commercial slowdown, and cases of racism worldwide.

Marco Wong, a local councilor in the Tuscan town of Prato, home to a large Chinese population, told The Guardian: “Parents aren’t sending their children to school if there are Chinese classmates and people are writing on the internet not to go to Chinese shops and restaurants.”

This is more than just a disease. It tests a society’s health systems, its government, politicians, the economy, and above all things, the soft power of their nations. For China, the opportunity is to re-engineer its perception by departing from the factory metaphor and reframe its soft power.

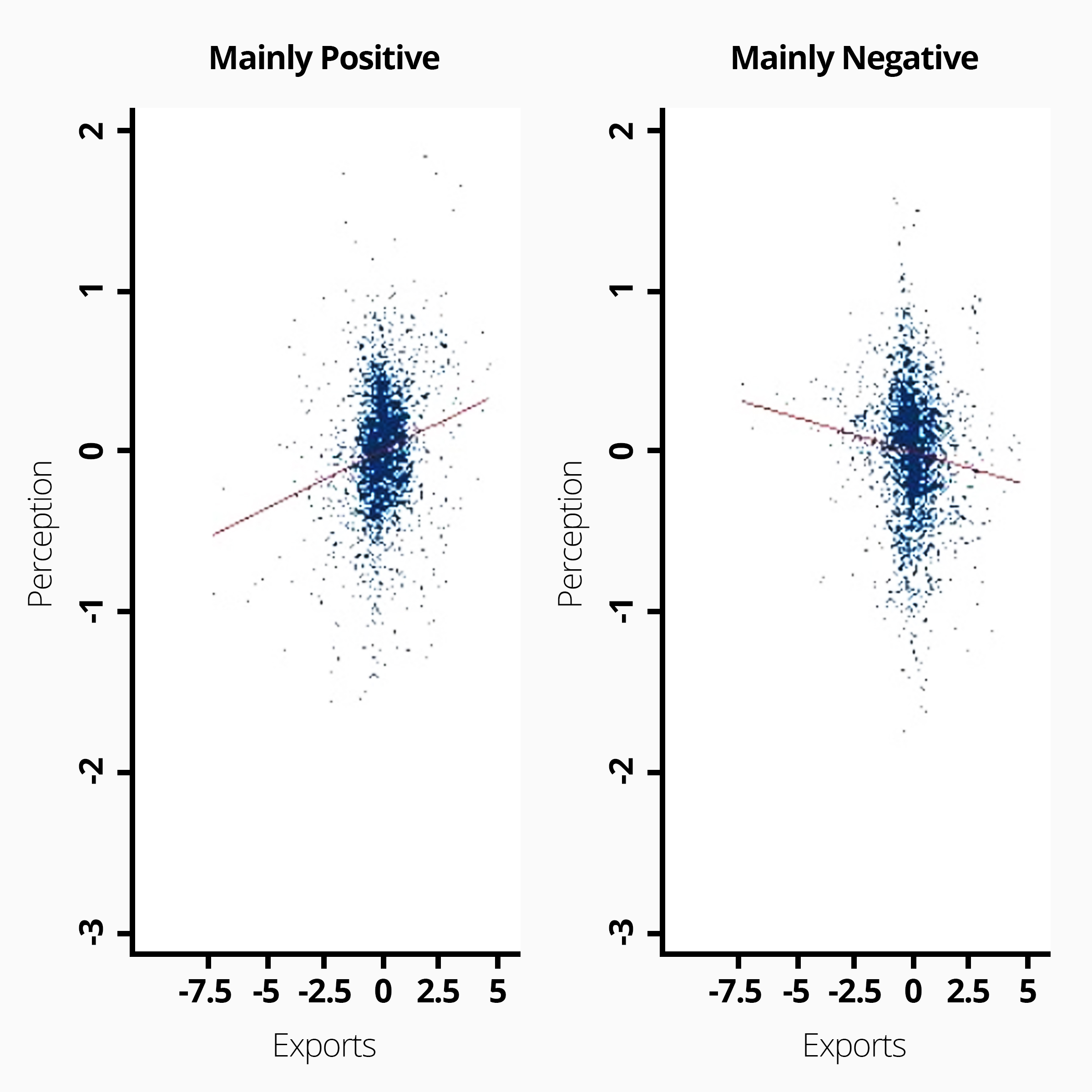

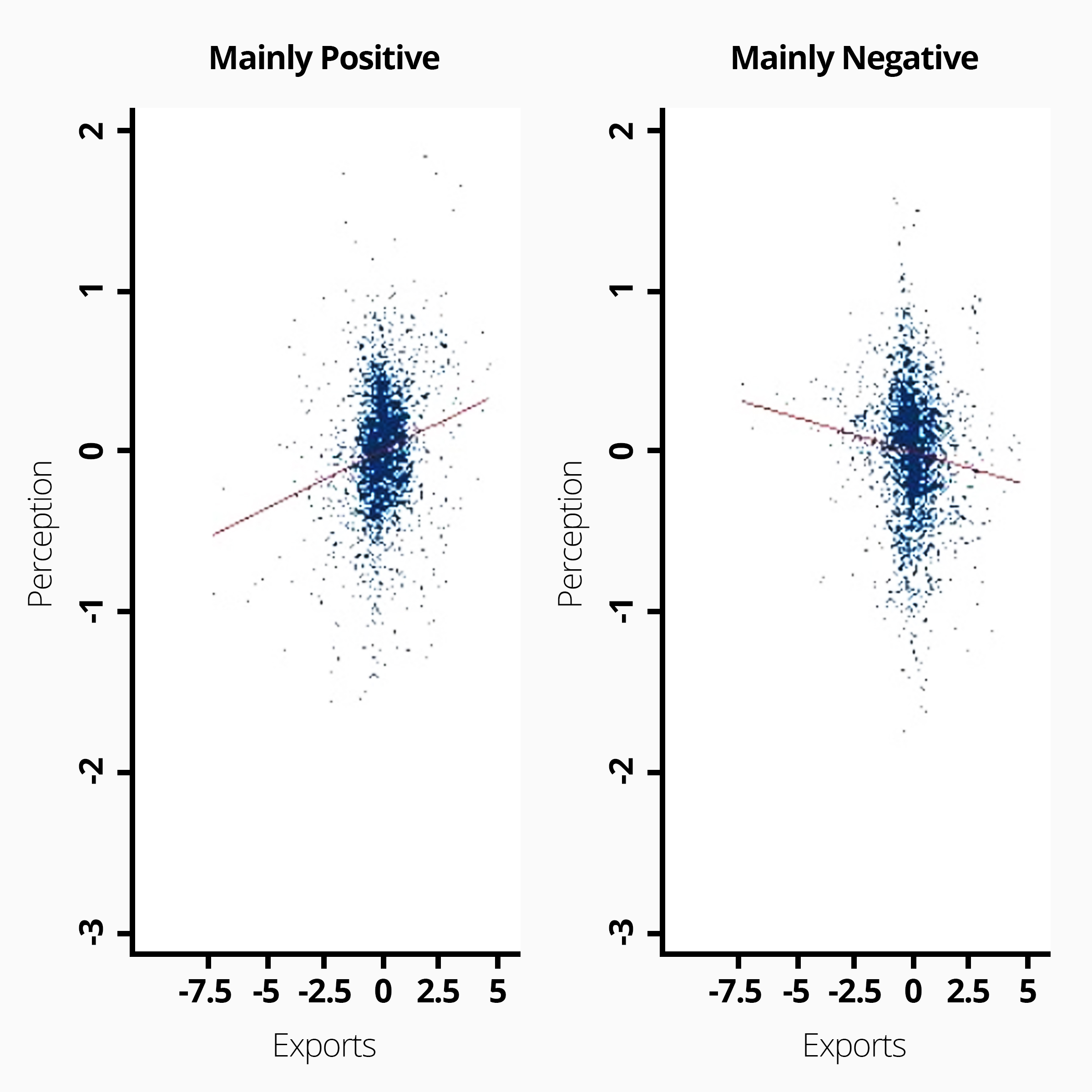

Soft power was defined by political scientist Joseph Nye as being a country’s ability to attract or persuade others to do its bidding, without having to resort to any form of coercion. As demonstrated by the University of California, Berkeley, soft power matters because countries that score high on cultural attractiveness export more. Every 1% net increase in soft power raises exports by around 0.8%.

Source: Like Me, Buy Me: The Effect of Soft Power on Exports; Centre for Economic Policy Research

In 2016, according to the Soft Power Today study, such a rise would have been worth £1.3bn for the UK, which recorded £197bn of foreign investment. While brand China may have considerably eroded its trustworthiness with a weak PR effort, its soft power was put to use to minimize the collateral effects from the pandemic and garner support from neighboring countries.

At one meeting, ASEAN foreign ministers joined hands with Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and shouted “Stay strong, Wuhan!” Stay strong, China! Stay strong, ASEAN!” Yet, nothing fuels and validates a nation-brand like the relationship between place and production.

Just like the symbiotic relationship between Meiji’s Japan and its subsequent “enlightened” tech brands, China has also made a tremendous effort to launching and sustaining successful global brands, even in spite of the heated trade war with the USA. Sportswear company Li Ning’s debut at NYFW and JD.com’s Nasdaq success story speak directly to that.

Nonetheless, brand China needs to be stronger than the summation of its commercial brands, turning “made in China” into a magnet for more positive exchanges and keeping its influence as strong as before the outbreak.

Chasing the “Chinese Dream” metaphor

According to Brand Finance’s CEO David Haigh, in relation to the 2019 Nation Brands study, “China is undergoing a meteoric rise on the global stage, rivaling the traditional nation brand powerhouses in the West. Despite economic and political challenges, China’s nation brand value has grown by 40% reaching $19.5 trillion, consistently outpacing the US and other major economies.”

But that was then. According to Hoover Institution Fellow Victor Davis Hanson, [China] “ruined their international brand,” having potential serious repercussions on its economy as foreign companies may exit. During an interview on live TV, Hanson added: “You think if you’re Italy or Switzerland or Germany or Australia, you really want to have your antibiotics produced in China when this is all over? If you’re a tourist and you went to China and somebody said there’s a virus contained but don’t worry, it’s contained — would you believe that?”

Commerce, not geopolitics or policymaking, is the path to prosperity and peace. It is the only space where our perpetual state of disagreement is settled through the voluntary exchange of goods and services. An empirical study published in the Review of Development Economics Journal confirmed that, as bilateral trade interdependence increases, so does the peace process.

In the case of brand China, the current strategy — encompassing an annual Chinese Brands Day every May 10th, and a nationwide China Council for Brand Development — is no longer enough. To heal the nation’s perception and sustain its role in our globalized economy, brand China needs to fix the problems it created. In the UK, for instance, several companies are retooling themselves to fight the pandemic and confer a leadership status to their nation of origin through this crisis.

Above and beyond, such initiatives reenergize the perception of British ingenuity that skyrocketed from the 19th century Manchester and was sustained by several other inventions like the ATM (1967), the World Wide Web (1989), Dolly, the First Mammal Clone (1996), and many others. These efforts, combined, should help provide plenty of soft power value and the genesis of what could be an entirely new business ecosystem; despite the UK Government’s questionable herd immunity strategy.

Precise orchestration of marketing, media, and branding tactics are needed for a meaningful, new narrative. In the case of China, having strong, global brands is not enough. Collectively, they must mean something more than their singular narratives. There’s no better time than now, there’s no better enemy for a heroic China than a virus. From unsettling “Chinese Whispers” to the “Chinese Dream”, a new metaphor able to infuse new meaning to its economy, is the nation brand’s imperative for future prosperity in the 21st century.

Cover image source: Adli Wahid

*By Sérgio Brodsky, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.

The digital-consumerist culture instigated, on the one hand, a sophisticated and constant need to articulate and maintain our personal identity through symbols and aesthetics of the branded world, and on the other, confronted us with the environmental and social effects this constant need entails. During the last half of the decade, it became clear that the only way to reconcile our need to keep consuming is to give back every time we take. As a result, sustainability initiatives came to be less than optional for luxury brands. But while sustainability seems to be now ever-present in the marketplace, it appears as though some brands master it more authentically than others. Some initiatives feel phony and inadequate, just as though they were told to jump on the bandwagon, while others are fresh, innovative, and deeply genuine. So what are the differences, and how can these insights help brand development?

“[A sustainable model] meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” — United Nations

Every initiative, narrative, and spokesperson contributes to a whole idea, feeling, and aspiration that we call a brand. Synchrony between brand elements is essential for a unified meaning, and so is the common goal that the brand helps its consumers navigate towards. To translate this into the marketers’ language: A successful brand needs a strongly defined brand essence to build tactical value-creation around. When the brand essence is well formulated, it serves as a lighthouse to storytelling, content creation, product development, and even pricing strategy. And here comes in sustainability, as a single, but crucial expression of the brand’s DNA.

Sustainability is defined by the United Nations as an idea and model that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” As easy as it sounds, in practice, implementation is intricate and puts even seasoned experts at unease. Brands, notably fashion brands, touch upon a long chain of operational stages from a single idea or trend, to design, production, sale, and even beyond if we consider after-consumption efforts. During all these stages, brands need to analyze their footprint to understand where and how they may impose harm on the environment, people, or other living creatures. Only then can a prioritization of initiatives and corrections begin to take place.

Amendments should not follow already existing practices of the marketplace but should be formed by the brand’s genuine philosophy. Hence, rather than compiling common tactics of competitors and emulating those, brands should return to their DNA. They must ask some questions and answer them truthfully:

- What is the change that we are pledged to bring from the beginning of our existence?

- What is the aspiration and hope we seek to evoke in our customers?

- What is the kind of life we seek to provide to our employees as a reflection of our philosophy?

In their best possible universe, how do individuals and communities interact, and how are the ideal environments envisioned? Once those questions are answered, that’s when companies should begin to critically assess what they can and should do for the sake of sustainable development. Laying out a map of the inflicted damages has to be first systemized, and then needs to be juxtaposed against the brand’s set of ideals. This step is crucial to generate sustainability initiatives that are authentically fitting and well-guided.

Patagonia, for example, is an eminent example of sustainability done well. Founded by Yvon Chouinard, a rock-climber and environmentalist, the company is an attestation to a slow-living lifestyle highlighting synchrony between nature and humans. They don’t preach change but pioneer it starting at home: The company offers on-site child care, maternal and paternal care, free yoga classes, and generous PTO packages. They have launched a line of repair programs, and infamous anti-consumption campaigns to cut down on consumer culture, or better, to reform that. “Balance” is their brand essence, which they seek to implement both in workers’ rights and environmental footprint. Rather than conforming to industry standards, Patagonia examines its chain of operations and molds them to reflect their own philosophy. Read about Patagonia’s famous “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign in Ivan Gurkov’s article on human relations management.

Sustainability is, after all, living our best self today, while preparing for the best possible tomorrow. Meanwhile, the meaning of “best” is hardly inherent, as ideas are not inherently good or bad, but we, humans charge them with values, associations, and judgments. And exactly this is what provides brands the possibility to form and shape the future according to their own understandings and hopes. When done consequently and consistently at all touchpoints, brands remain authentic and more complex. A footprint due to operations will always exist, and the ultimate aim is not to erase it but to minimize and shape it. It would be hypocritical to state that sustainability is not a commercial opportunity in today’s marketplace, however, it is also an opportunity to lead everyday practice towards a world better lived.

Cover image source: Benjamin Davies

*By Sara Bernát, originally featured on Brandingmag.com.